|

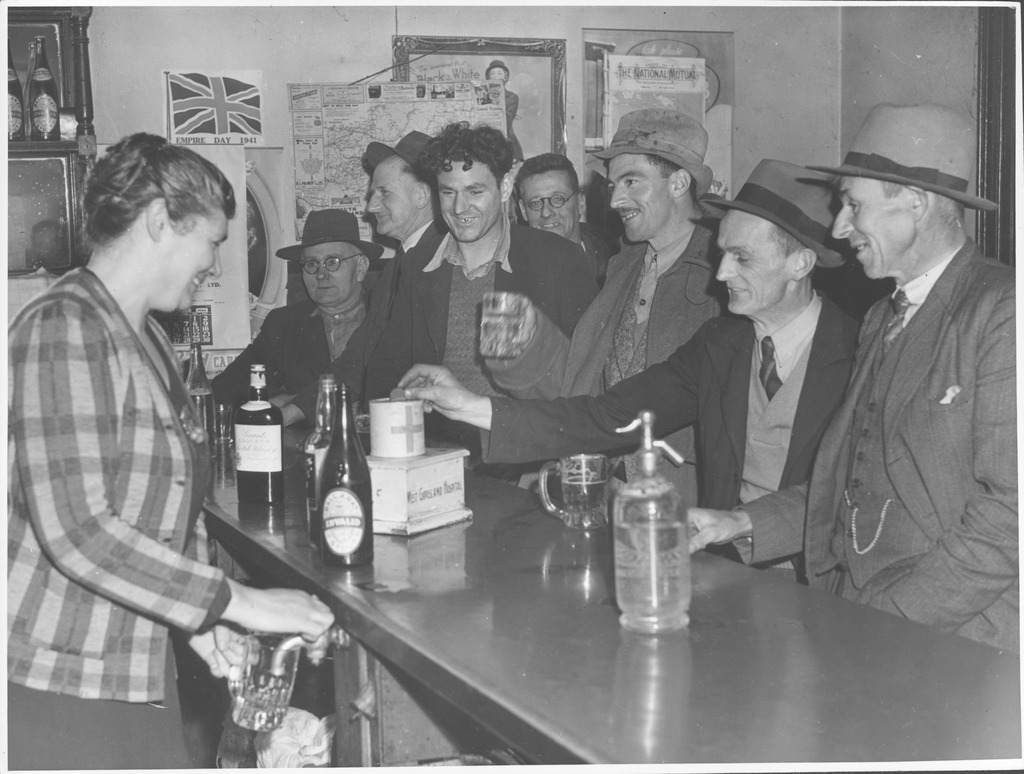

| Saloon Bar - Royal Hotel, Randwick | NSW Police Forensic Photography Archive Sydney |

Many highly technical fields of research are deeply significant to the every day lives of many people: from health research, to risk analysis, economic research, IT security, political sciences, and media studies.

Everyone is trying to navigate decisions about what medicine to take, whether to update their computer, how to save for retirement, how to make decisions when they vote, how to interpret the news, what book or film to watch and how to think about it when they do.

Projects like The Conversation, 3MT (heats are on at La Trobe right now!), blogs, TV documentaries, academic Twitter, and mass media paperbacks like Twitter and Teargas, Doughnut Economics and Testosterone Rex, are all fantastic examples of ways to help non-specialists engage with cutting edge research and big ideas. (I have just read the 3 listed books, even though I’m not an information security expert, an economist, or a behavioral scientist, and, in fact, stopped studying any of these subjects half-way through high school).

The ‘pub test’ is an Australian term for the idea that expert or complex ideas that impact people’s lives need to be comprehensible to an ‘ordinary’ person. This is a longstanding tradition, like the early-twentieth-century legal idea of a ‘reasonable person’, also known as the ‘man on the Clapham omnibus'. This ‘man’ probably doesn’t have a higher degree, but is reasonably intelligent, a reliable worker, takes public transport, keeps up with the news, and is going about his daily business. In Melbourne, where La Trobe is based, this person turns up in legal decisions riding on ‘a Bourke St tram’.

Not so long ago, there was a major kerfuffle in the media when a government minister made fun of ‘obscure’ academic projects for research funding which, he felt, would not pass a ‘pub test’ and therefore shouldn’t be funded. Before that, there was a similar kerfuffle when another government minister made fun of a grant for what he said was an irrelevant and obscure philosophy project (which of course turned out to be actually quite relevant after all).

So, the pressure for academics to succeed in the ‘pub test’ is both moral and political in Australia.

However, the pub test itself is a terrible way to help people get involved in big research questions, and a terrible way to include non-experts. Why? Because pubs have not historically been inclusive places in Australia.

The pub has been imagined as ‘a place of egalitarianism and mateship’ at precisely the same time as it excluded women and non-white drinkers. The pub test assumes it was a place of conversation and collegiality, even as, for most of the 20th century, it was the place of the ‘6 o’clock swill’ where ‘anything which interfered with the fast and efficient dispensing of drink was thrown out… [so] the pub was no longer a social centre for leisurely drinking and recreation’ (p. 250). The public bar at 6 o'clock looked like a sea of white men, cigarettes and pints.

|

Worse, Indigenous Australians were excluded from pubs by law, including Indigenous Anzacs, the original mates, who returned from the front to be excluded from pubs (as well as the government support their white colleagues received, let alone a right to citizenship.)

Pubs that focused on drinking rather than food have also always excluded those who don't drink, including those who don't drink for religious reasons, like Muslims and Baptists, and those who can't drink for health reasons (yet another way that pregnant women are disadvantaged in academia).

The pub test is therefore inherently racist and misogynist. It implies that the most important non-specialist is a white man. So, let’s not do that.

There are other ways of talking about the idea that your research should be comprehensible to a lay audience: for example ‘could you explain it to your granny?’ (see also here and here). I’m not a fan of the granny test either, as it suggests older women are stupid and uneducated. In real life, we see how many older women ‘computers’ were squeezed out of computing and mathematics (or see this Twitter thread about expert grandmothers) and therefore probably know more about science than I do. I know so many grannies who are experts in child psychology, Hebrew phonology, ancient Latin and the novels of Henry James.

Some other people have suggested a better test is: 'Explain your project to a customs agent'. As this article puts it:

can you successfully explain [your project] to an TSA [US customs] official—someone who not only might have no background in science, but also strongly suspects that you might be a national security threat? Can you justify your research in the face of questions like “What are you doing?” or “Why are you doing it?” or “Why are you taking that onto a plane?”I like this idea—why are you travelling with a Tupperware box full of frogs, a 3D printed mouse penis, a massive encrypted hard disk, or twenty volumes of 1880s Colombian cookbooks? Why do you have a search history full of extremist chat rooms, or spells, or Nazi propaganda movies? And why are returning to the country again with yet another wetsuit possibly contaminated with four kinds of parasite, or a machete?

Non-experts who are smart and a little bit interested deserve to know a little bit about your research and how it might impact them. An informed citizen is a citizen better able to make good choices—and the woman on the Bourke St tram, the undergraduate in your tutorial, the customs officer at the airport, and the reader of The Conversation all benefit from having an idea of what you study and why it matters.

You could even talk about it with your friends in a pub, now that food and soft drinks are widely available and the rules for who can be there have changed!

---------------------------------------

Katherine Firth has worked as an academic, an Academic Skills advisor and as an academic manager. She is currently a lecturer in the Research Education and Development Team at La Trobe. She also runs a doctoral writing blog at Research Degree Voodoo.

She has won an academic award for her work on Thesis Boot Camp at the University of Melbourne.

Her research interests are literature, musicology, cultural history, and academic writing.

Comments